Writing in Faux Cafes

Noelle Sterne

I sit at a table in the Starbucks at the local mall. Finally, having gotten out of the house, I’d lugged a heavy tote bag of everything needed for the self-promise I’m determined to keep after much procrastinating: to polish off my latest how-to article. I spread out the files and notes and line up my battalion of pens, paper clips, and post-its. My clipboard is open for business.Writing in the mall Starbucks is the latest in a long line of faux cafés that track my writing evolution. Of course, cafés of one type or another, in exotic locales, off the local highway, or around the corner, are nothing new for writers. Hemingway haunted cafés in Paris and Madrid. Natalie Goldberg chronicled her personal odyssey of journal-writing in coffee houses and diners for us to model. J. K. Rowling produced the empire-spawning Harry Potter manuscripts in Edinburgh cafés, now hot tourist stops.

Today, I can’t get myself to pull out the how-to article. Instead, the pull is too strong to write about writing in ersatz cafés.

Party Cake

My first so-called café, during graduate school studying English literature at Columbia University in New York City, was a coarse neighborhood bakery. The small shop, with the drooling name Party Cake, was part of a chain that specialized in fill-in-the-blank birthday cakes piped with pastel green, pink, and blue teeth-gritting sugar rosettes. The cakes were always displayed en masse in the window, with a rotating line of additional cakes featuring seasonal rosettes. In the early mornings, I’d ignore the unending piles of books for course reading on my desk at home and slip out.

At the counter, staring at the pastries and cookies by the pound, I’d give my order. Always the same: dark coffee and a seeded roll, light on the butter, please. I’d balance these in one hand, the other clutching my writing tote, and corral one of the three tables squeezed in near the counter. I made sure to get there early before some retiree set up camp with his New York Post.

Arranging my so-called breakfast and materials carefully, I’d try not to get butter on my clipboard as I poured out, usually, a cathartic essay anathema to the current strict training in proper academic writing. Between paragraphs of a raw first draft I was sure were consummate gold and planned to whip right out to The New Yorker, I sipped and watched the subway commuters and bank clerks come in for takeout coffee, bagels, and Danish.

Party Cake held me well for a few years. When it closed, making way for a jazz bar as the neighborhood upscaled, I tried the corner Greek diner. But it was only good for the more rote aspects of revising, which, after mounting rejections, I’d finally accepted as essential. The booths lacked coziness, the greasily handsome waiters-owners unnerved me, and the incessant rolled-r shouts of “Cupa creamo!” for customers who ordered the daily flavored cornstarch soup broke my concentration.

The Hungarian

Then, after a modest triumph of a story published in a small magazine, I graduated to an authentic replica (so I imagined) of an old-world café. Three blocks away from my apartment, an anomaly on a graceless, potholed main street between rundown storefronts, the Hungarian Pastry Shop sat across the boulevard from the equally unlikely majestic (faux) Gothic Revival Episcopal cathedral perpetually in construction, St. John the Divine.

At the Hungarian, as the regulars called it, in one section a knot of middle-class Columbia students masqueraded as European bohemians. They spent all day—who knows when they ever attended classes—arguing fiercely about newly-discovered Nietzsche and Schopenhauer, the compelling virtues of socialism, and the eschatological implications of reverse universes.

In another of the Hungarian’s sections, a few young mothers, assistant professors’ wives, parked their awkward baby buggies and furtively grabbed confections before the next diaper change.

In a third area, would-be writers, unperturbed by the dim light, sat for hours. They projected insulated solitude—bookbags and papers propped on all the chairs at their tables, notebooks pointedly open, and faces chronically scowled—so no one would sit down, start a conversation, or try to pick them up.

Feeling like I’d made my writing bones, I joined this latter group and ordered my new indulgence: strong coffee in a heavy restaurant mug, worn down from too many washings, and a made-from-scratch lightly frosted bear claw. I learned the art of making the coffee and claw last for hours, and sometimes the wispy waitress would drift by and kindly pour a refill. I went to the Hungarian regularly between classes, to write new pieces and assiduously refine others. If I missed more than two days, I felt homesick for the Hungarian.

At the university I fulfilled the requisite courses, got the requisite degrees, and went on to teach, edit, and guide other graduate students through their ordeals. But my heart never left the Hungarian.

No Seating

After moving to South Florida, I lost sight of cafés, faux as they may have been. To write in a Bagel Crib run by transplanted Bronxites wearing dirty white full-length aprons and rasping tongue-on-rye orders wasn’t quite the same. Tables too close, patrons too loud, and Entenmann’s doughnuts no match for home-made Hungarian bear claws.

I continued to write spottily, weaning reluctantly from clipboard and pens to desktop computer, and grabbed guilty minutes at home between always-pressing client projects. But the cafés remained golden in a corner of my memory. They signaled not only my first serious writing but the all-important declaration of making regular time for it.

And now, in a land far away, almost hopelessly homogenized with fake Mediterranean redundant pharmacies, supermarkets, convenience stores, franchised hair salons, and malls growing concrete extensions like giant squids, I’ve rediscovered my café. Yes, mutated with the times, and undeniably mock, but the closest attainable.

Starbucks

So here I sit in the mall Starbucks. It’s become for me the physical and metaphorical setting to explore the ever-compelling and elusive twin processes of writing and stalling. Sitting here is a microcosm of negotiating the world, getting to better know myself in it, and continuing to fight for—even sometimes win—mental writing space and consistent production.

The Starbucks occupies a public court at one end of the mall, a circular oasis ringed with shops. A three-story atrium rises above the logoed kiosk surrounded by tables and chairs, a skylight at the top letting in some rare natural light. I look up and up and sigh. A whole two hours. After basking in a moment of self-congratulation, I pick up my pen.

Instant diversions appear, though, as people parade from one shop to the next. Peeping Tomasina, I marvel at their struts, shuffles, jaunts, shapes, sizes, expressions, mannerisms, getups. Gotta put somewhere that older woman dressed like Fifth Avenue, looking down at all the flip-flopped t-shirted shoppers, her designer handbag hanging conspicuously on her arm. And that nymph in the short orange dress and foot-high stilettos as she pretends to be absorbed in her phone and unaware of all the leers.

The cavernous collective noise bounces through the atrium, and I catch slivers of voices floating to the skylight—tinkling giggles of girlfriends, shards of couples’ mutual reprimands, and barks of exasperated parents at unruly children. Wish I had the latest recorder app in my brain for later playback.

The afternoon load of seniors, whose special condo bus takes them on the Outing To The Mall, have managed to commandeer almost all the tables. Nevertheless, I found mine, small and a little outside the main area. Best of all, it’s half-hidden, buttressed against one of the hefty square columns that support the three stories to the skylight.

My table has only two chairs; me in one and my sprawling tote usurping the other (the Hungarian taught me well). The tote wards off any matron carting shiny Nordstrom’s shopping bags, bending too near, and asking too brightly, “Is this seat taken?”

In this almost-office, if I lean a little to either side, procrastinating I can spy on the parade. Positioning myself squarely in front of the column, I’ve got privacy. My current treat is a slab of reduced-fat coffee cake—pale reminder of the exquisite Hungarian—and a monstrous venti latté—a term I only recently learned to use with nonchalance.

I settle in and place the cake, already bleeding through the bag despite the reduced-fat declaration, on a wad of napkins and open the giant recycled cardboard coffee container. My pens and clipboard wait ready, and I take a bite and a sip. Spurred by the mildly oily chunk and soul-satisfying taste of milky espresso, I choose a pen and begin to write.

Finally, the smart shops don’t beckon, my chronically impossible list of to-dos at home recedes, the piled-up client work ceases its demands, and even the procession of mallers finally holds no appeal.

Here, in the expanding present, writing, time stops and bliss suffuses me.

If it takes a slab of insipid cake, a spike of diluted espresso, and an overconsumerized mall to remind me, so be it. In each of my faux cafés, despite waves of chronic avoidance, ever-layering responsibilities, and ever-lessening time, the lesson has resurfaced and deepened.

I offer it to you—find your equivalent of my café, in whatever neighborhood or country, in whatever creative passion. Honor your cherished dreams, desires, and gifts. And let yourself feel, as I do sitting in the Starbucks faux café, the perfect reward.

-

Let's Get Social

-

What Do You Think?

-

-

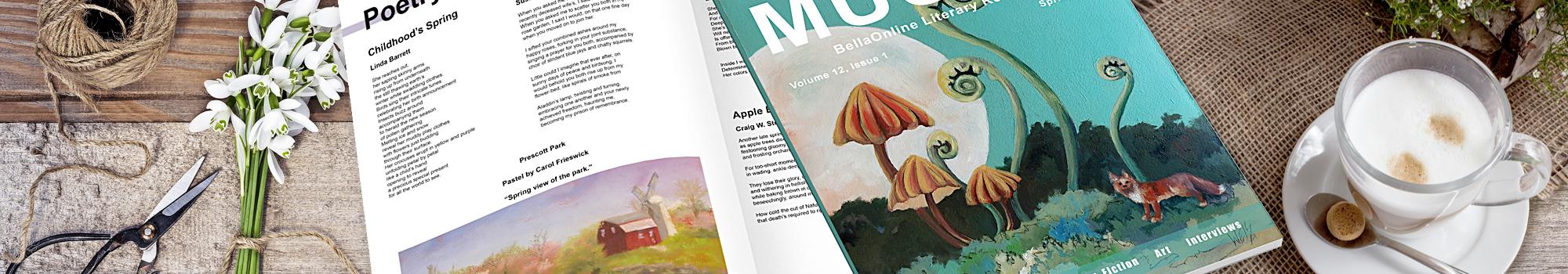

MUSED Newsletter

Stay up to date with the latest from MUSED